The

early Hebrew version of the book of Job contained the word

layisch, which meant "lion." Through either misunderstanding or faulty transcription, this word was translated into Greek as

murmêkoleôn ("ant-lion") for the

Septuagint, an early Greek-Christian Bible. This ant-lion (or ant-dog, as it sometimes appeared later) made its way into the symbolic Greek-Christian book called

Physiologus, an anonymous text written in the 3rd or 4th century (Kevan 1992).

Here's the relevant passage:

Eliphaz the king of the Temanites said, 'The ant-lion perished because it had no food.'

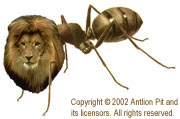

The Physiologus said: 'It had the face (or fore-part) of a lion and the hinder parts of an ant. Its father eats flesh, but its mother grains.' If they engender the ant-lion, they engender a thing of two natures, such that it cannot eat flesh because of the nature of its mother, nor grains because of the nature of its father. It perishes, therefore, because it has no nutriment. So is every double-minded man; unstable in all his ways. . . (Kevan 1992)

The concept of the ant-lion as the offspring of lion and ant soon proved too fantastic for the Physiologus editors, who mostly eliminated the ant-lion from later versions. Nevertheless, the moral of the story of the mythical ant-lion remained entrenched in tradition, appearing in early naturalist literature and medieval bestiaries (Kevan 1992).

Gerhardt, M. I. 1965. The ant-lion nature study on the interpretation of a biblical text, from the Physiologus to Albert the Great. Vivarium. 3: p.1-23

Kevan, D. K. McE. 1992. Antlion ante Linné: [Myrmekoleon] to Myrmeleon (Insecta: Neuroptera: Myrmeleonidae [sic]). Pp. 203-232 in Current Research in Neuropterology. Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Neuropterology [Symposium held in Bagnères-de-Luchon, France, 1991.] M. Canard, H. Aspöck, and M. W. Mansell, eds. Toulouse.