Lions called ants

The fantastic story of the gold-digging "ant-lions" of India has a long and complicated history. The source might be the great Hindu (Sanskrit) epic, the Mahâbhârata (with origins around 1000 B.C.E.), which makes reference to ants that excavated gold (Kevan 1992). The earlest surviving European account of khrusôn murmêkôn (gold ants)—or murmêkoleôntes (ant-lions) as they were called much later—is found in the Historiês Apódexis of Hêródotos (ca. 430 B.C.E.). Druce (1923) retells the story of these unusually large and vicious "ants":

[The] scene is laid in a northern district of India, where there is a desert in which ants abound in size somewhat less than dogs but larger than foxes. They burrow under ground and heap up the sand which contains gold. The Indians go to the desert to collect this sand, each man provided with three camels harnessed together side by side, that is on either side a male, and in the middle a female on which he rides. The female must only just have been parted from her recently-born young. The Indians being thus equipped set out at such a time that they will arrive at the hottest hour of the day, for during the greatest heat the ants hide underground. They bring with them sacks which they fill with the sand and then retun as fast as they can. For the ants detect them by the smell and pursue them, so that if the Indians do not get a good start while the ants are assembling, not a man could be saved. The male camels in time slacken their pace, but the females mindful of their young hasten on; and in this way the Indians return safely with their gold (pp. 354-355).

This story of giant ants that dig up and fiercely protect their gold passed through various hands, inluding those of Nearchus (4th century B.C.E.) and Megasthenes (3rd century B.C.E.). Nearchus is quoted as having "seen the skins of ants which dig up gold, as large as the skins of leopards." (Druce 1923, p. 355). According to Druce (1923) the term "ant-lion" appears around the 2nd century B.C.E. In his description of the lions of Arabia, Agatharchides "actually mentions ant-lions by their Greek name (mirmecoleones) and says that in appearance most of them differ in no way from the other lions; and Strabo when describing the coasts adjacent to the Arabian Gulf says that the country abounds with elephants and lions called ants." (pp. 355-356).

The story was modified and embellished after the beginning of the Christian era, often by replacing camels with horses, and increasing the size of the ant-like creatures. In Peri Zôôn Idiotêtos (or De Natura Animalium), ca. 200, Aelian referred to "gold-digging ant-lions." In the 2nd and 3rd centuries, Philostratos and Solinus placed the creatures in Ethiopia as well as in India. And it was Solinus who, in his Collectrania Rerum Memorabilium (later called Polyhistor), increased the size of the creatures to that of mastiff dogs and added that they had talons like those of lions, with which to scoop up the gold (Kevan 1992).

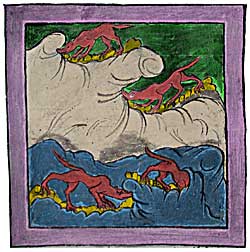

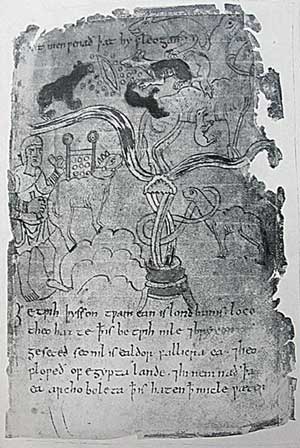

The best surviving illustrations of the story come from two 10th century Anglo-Saxon manuscripts of the De Rebus in Oriente Mirabilibus in the British Library, London. The manuscripts depict the classic gold-digging "Indian ants," as well as the camels used to steal the gold (see Figures 1, 2, and 3). The text says that the ants are as big as dogs, are red and black, and have feet like locusts. The gold-seeking men bring both male and female camels and load the gold on the females. These then hasten back to their young foals, but the males left behind are discovered by the ants and devoured (Druce 1923).

|

|

| Figure 1. The "Indian ants" digging for gold. From De Rebus in Oriente Mirabilibus, a late 10th Century Anglo-Saxon and Latin MS (British Library, London, Cotton Tiberius Bv). (Druce 1923 and Kevan 1992). [Colors added by the editor, based on a description by Druce (1923)] | Figure 2. A gold robber escaping with a sack of gold on a female camel hastening to its unfed calf while the "ant" creatures attack and devour an abandoned male camel. From De Rebus in Oriente Mirabilibus, a late 10th Century Anglo-Saxon and Latin MS (British Library, London, Cotton Tiberius Bv). (Druce 1923 and Kevan 1992). [Colors added by the editor, based on a description by Druce (1923)] |

| Figure 3. Here the scenes of Figures 1 and 2 are combined into one picture. At the upper left is a hole in the ground with about twenty lumps of gold lying about. On either side of the hole are the "ants" guarding the gold. To the right is the male camel being attacked by three "ants," flying at its belly, back, and flank. A winding river crosses the middle of the picture, and below the river on the far right is a young camel tethered to a tree. On the far left is a man with a female camel. On its back is a square structure in which are visible nine lumps of gold. From De Rebus in Oriente Mirabilibus, a late 10th Century Anglo-Saxon and Latin MS (British Library, London, Cotton Vitellius A xv). (Druce 1923 and Kevan 1992). |

|

Variations of these ant-lion stories would reappear in medieval Christian bestiaries during the 12th and 13th centuries. As the bestiaries drifted from their sources, geographically and historically, ant-lions were eventually replaced by insect ants (Kevan 1992).

Mystery solved?

Controversy over the real identity of the Indian gold-digging ants (or ant-lions) has continued until the present. Scholars have suggested a variety of animals including dogs, marmots, pangolins, mongooses, and the badger-like ratel (Kevan 1992).

In

|

|

| Figure 5. A marmot, Marmota caudata. |

While this discovery may explain the centuries-old mystery, Peissel would like to test his findings with a full archeological and geological survey. The area lies on the tense border between Pakistan and India, however, so the political climate may prevent such work. Says Peissel: "It's right in the line of fire of both sides. There was gunfire when we were there. The locals tell us that the marmots are dwindling. The Indian soldiers are constantly taking potshots at them" (Simons 1996).